The Pyre

Cast

Conception, direction, choreography et scenography Gisèle Vienne

Music written by, live performance and diffusion KTL (Stephen O’Malley & Peter Rehberg) except the song Back Eyed Dog by Nick Drake from the album Made to love magic *

Text Dennis Cooper

Light Patrick Riou

Video Gisèle Vienne & Patrick Riou in collaboration with Robin Kobrynski

Created in collaboration with and performed by Anja Röttgerkamp and alternaly by Lounès Pezet, Léon Rubbens or Kamiel Van Looy

With the voice of Dennis Cooper

Costums José Enrique Ona Selfa

Make-up Mélanie Gerbeaux

Sound spazialisation IRCAM Manuel Poletti

Set conception LEDs Designgroup professional GmbH/ LED Lightdesign

Other set elements Espace et Cie

P.O.L published the special edition of The Pyre for the show

Technical coordination from the team of the Opéra de Lille

Computer collaboration IRCAM Thomas Goepfer

Technical management Richard Pierre

Sound management Gérard d’Elia or Adrien Michel

Light/video management Patrick Riou or Arnaud Lavisse

Stage management David Jourdain

3D plans coordination Rémi Brabis

Scenography assistant Marc Le Hingrat

Production, booking & administration PLATÔ Séverine Péan, Carine Hily et Julie Le Gall

Production & international booking Alma Office Anne-Lise Gobin et Alix Sarrade

* Written by Nick Drake / Produced by Joe Boyd and John Wood /Published by Warlock Music Ltd. © 2004 Universal Island Records Ltd. A Universal Music Company

“To Jonathan & Jean-Luc”

Acknowledgements to La Monnaie/ De Munt et le Kaaitheater (Brussels) for putting their rehearsal studios at our disposal, Jonathan Capdevielle, Nicolas Herlin, Alexandre Vienne, Anne Mousselet & Bureau Cassiopée for the production work during the season 2011/2012

Partners

Executive producer DACM

Coproducers Opéra de Lille // Le Parvis, Scène Nationale de Tarbes-Pyrénées // IRCAM & Les Spectacles Vivants-Centre Pompidou in the frame of Festival Manifeste 2013 // La Comédie de Caen Centre Dramatique National de Normandie // Bonlieu Scène nationale Annecy & La Bâtie, Festival de Genève in the frame of the project PACT beneficary from FEDER with the funds INTERREG IV A France-Suisse // Arts 276 – Automne en Normandie // Scène nationale d’Évreux // Centre de Développement Chorégraphique Toulouse-Midi-Pyrénées (accueil en résidence) // Centre Dramatique National Orléans/Loiret/Centre // Centre Chorégraphique National d’Orléans // Le Maillon, Théâtre de Strasbourg − Scène européenne // Pôle Sud // Malta Festival Poznań 2013 // Holland Festival // Internationales Sommerfestival − Kampnagel // Künstlerhaus Mousonturm – Francfort // Next Festival 06, Eurometropolis Lille-Kortrijk-Tournai & Valenciennes // BIT Teatergarasjen – Bergen // IDEOLOGIC ORGAN (FR) // Designgroup Professional GmbH

With the support for the creation of Festival Actoral

With the support of DICRéAM and in collaboration with Kunstencentrum BUDA in Kortrijk

The company was supported by DRAC Rhône-Alpes / Ministère de la culture et de la communication, Région Rhône-Alpes in the frame of the support to artistic teams and in the frame of SCAN and FIACRE, and by Institut Français for international touring during the creation of The Pyre.

Within the framework of the project TRANSFABRIK « TRANSFABRIK has been initiated by Institut Français in collaboration with Goethe Institut and with the support of Hauptstadtkulturfonds Berlin, Ministère des Affaires Étrangères, Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication and OFAJ. With the support of Total and of SACD. Within the framework of l’Année franco-allemande -Cinquantenaire du Traité de l’Élysée »

Partners Pact Zollverein (Essen) // HAU (Berlin) // Kampnagel (Hambourg) // Théâtre de la Cité Internationale (Paris) // Centre Pompidou (Metz) // Le Quartz Scène nationale (Brest) // Festival Perspectives (Sarrebruck) // Collège des Bernardins (Paris) // Festival June Events / CDC Atelier de Paris – Carolyn Carlson // Centre Pompidou (Paris) / Les spectacles vivants // Rencontres Internationales de Seine-Saint-Denis

Coproduction of House of Fire with the support of the Culture Programme of the European Union

PREMIERE On 29th, 30th et 31st May and 1st June 2013 in Centre Pompidou à Paris, in the frame of Festival Manifeste 2013

Presentation

Throughout the composing of this new piece, we have attempted to push the work’s always intense and complex relationship to text – a relationship that has guided every one of my collaborations with American writer Dennis Cooper since 2004 – to its limit. The goal is to bring this impossible and complicated relationship with words to its paroxysm. The text being staged almost needs to be hidden. Consequently, we must develop the way in which it can shine through even suffocating movement. The characters we have portrayed in our work have always struggled to express themselves, especially out loud. The two characters in this performance, a dancer and a boy, are mute, and their inability to speak reflects this impossible relationship to the text. The text, which is therefore and necessarily the subtext will, for the first time, be given to the spectator in the form of a novella to be read at the end of the show.

Our works, regardless of their individual natures, have always mixed abstract, figurative, and narrative writing. Here, we wish to question this writing’s fundamental relationship to dance through a performance where abstraction literally reflects the characters’ need to escape from their reality: in this case fictional. Their performance, which will at first oscillate between a state of embodiment and that of disembodiment, through movement that both represents the body’s transfiguration and explores the tension between these two states, will attempt to disturb the status of everything that is represented – the characters’ very reality – in order to give their world a mythical dimension.

SACRED HORROR

“…but, the dance of the future will once again become a highly religious art, like in ancient Greece. For, an art that is not religious is not an art, it is a banal commodity.” Isadora Duncan, Der Tanz der Zukunft. 1903.

The transfiguration of the dancer into an image is part of the long history of works that play with the relationship between human beings and illusions. The notion of the living body as a tableau has spawned a form that stands at the juncture of choreography, theatre, performance, painting, sculpture and photography. From ancient Greek culture until now, the premise of a living body as tableau has continually been reincarnated into new forms, from Phryne and Lady Hamilton’s poses in the early 19th century to voguing in the late 1980s, among others. One wonders if this “rhetoric of the tableau vivant (an effigy that appears to be alive; a woman who freezes into a tableau) can shed new light on the tableau and its effect today, through which not only the vision of images, but also that of bodies, might pass.” (Bernard Vouilloux, Le Tableau Vivant, 2002).

First of all, the isolation of the dancer enables us to work on the glorified body, that is to say, of a mere mortal transfigured into a divine figure, raised to the level of an icon – in our case a 21st century icon. This body, conveying both the absence and presence of a goddess, or of fantasy, as well as the silence that emanates from the seemingly empty body, elicits a feeling of “sacred horror” as Paul Valéry would say.

We are endeavouring to question a stable, assured and reassuring view of the visible object and to work on this paradoxical metamorphosis of the body and the figure, causing them to flow into one another and cause an interplay between both states. We do not know what we are seeing, and this absence of knowledge disrupts our vision.

In this way, the body (as well as the entire show) might sometimes appear to be a tableau to the audience. The transfiguration that has taken hold of that body, for just a moment, constitutes an image.

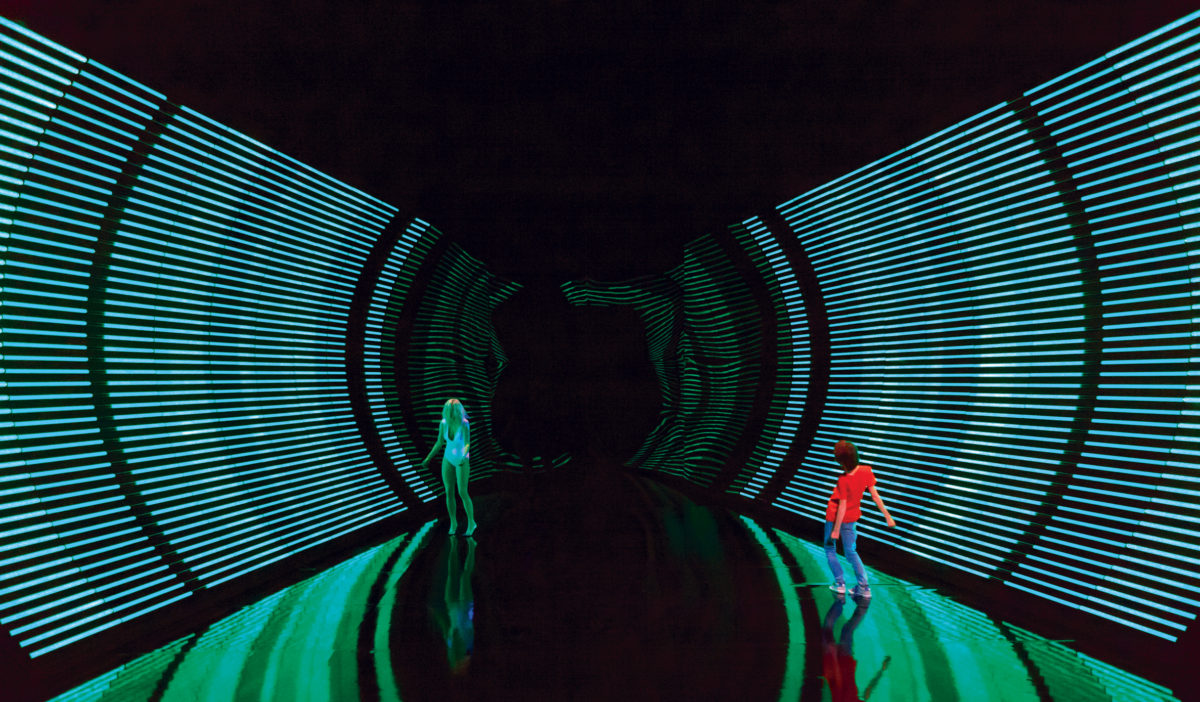

In this show, time unfolds very visibly through the articulation of choreography, space (a light-sculpture), and music. On stage, the dancer initially exists in a space that consists of nothing but LEDs, making direct reference to the way contemporary urban exteriors and interiors, like nightclubs, are lit. Despite these references, the space often feels abstract, generating an oscillation of its very status. The orchestration of the lighting also provokes, through its movement, an extension of the choreographic work and can generate an uncanny and sublimating chromatic effect by erasing any realistic vision of flesh. This perception evokes a relationship to the body that one can experience quite often in life when bodies find themselves “on stage” amongst the different architectures and styles of lighting that are characteristic of modern-day cities. Lastly, this excess of light is not without a reference to George Bataille’s The Accursed Share and to its notion of “improductive expenditure” (dépense improductive), the supreme example of which is the sun.

The soundscape created by Peter Rehberg and Stephen O’Malley incorporates invisible and absent elements – ghosts, one might say. It proceeds from simulated diegetic sounds (which are part of the action) interwoven with real sounds, and of a musical creation that makes up an extra-diegetic sound score. This composition dizzyingly sculpts the space on stage and generates the impression of great spatial depth, which the light-sculpture activates by evoking the illusion of a tunnel, whose depth also results in a play of reflections.

Through these different media, our aim is to develop and shatter – without looking to resolve – the exceptional intensity that can arise from the dialectical tension between presence and absence, as well as from the characters that are seeking flight.

WITHDRAWAL

“…the human body is easily made into a medium for psychic expression, while also being both a mechanical and mathematical construction so that, throughout stylistic transformations and over time, one or another of these aspects has found itself to be emphasized or amplified.”

Oskar Schlemmer, Mechanisches Ballett, Tanz und Reigen, 1927.

As I said, our style of writing for the stage has developed and evolved throughout our past performances and is composed of abstract, figurative and narrative elements. As a mirror of how we perceive reality, we feel that assembling these different types of representation will foster a more exhaustive perception of the world.

We are particularly interested in questioning this rapport through a performance that is first and foremost choreographic, involving abstract writing, while also drawing on a more theatrical and narrative tradition, acknowledging the role that the dancing body has adopted throughout its history. The notion of the body as metaphor, i.e. of a body that is apparently disembodied while also evoking its own image, has also been explored and represented in the performance context via numerous forms of incarnation. These range from attempts to embody this idea in the performance at large to using performers themselves as its representation. This question, which is intrinsic to dance, highlights an underlying paradox. If dance is seen as human expression, it can just as easily be seen as a totally abstract art. It is, in fact, quite difficult to perceive the body solely as a pure abstraction. We wish to dwell on this fantasy of an abstract body, and to depict its inevitably concrete and signifying quality, as well as to probe the relationship between dance and meaning.

These different modes of representation initially stem from abstract writing, enabling truly abstract movement by isolating the dancer, the space and the sound from their context, if only to better plunge them back into their context at the end of the piece. This form of writing is not without its references to forms of dance that have emerged from social contexts where dance would appear to be a vital means of escape.

Our new show’s conclusion, which unfolds in a more narrative manner, therefore questions the abstract writing employed up until then, relocating it in a narrative context that is far more reminiscent of a real context. At that point, abstraction appears as a means for the dancer and the young boy to ‘withdraw’ (s’abstraire) from the narrative context in which her so-called ‘character’ has been placed.

Dennis Cooper’s text, which until this point has inaudibly and unidentifiably guided the show, bursts into the narrative. Dennis Cooper has written a novella for this project, and this show is a theatrical version of it – although this only becomes clear as the show draws to a close.

In the last part of the show, the two characters are more explicitly placed in greater tension within the narrative, which contains the dramatic content of their reality. The narrative contagion contaminates all the elements of the theatrical writing, which are then put into perspective, and which now appear more figurative, taking on new meanings.

The final and pivotal movement reveals the show’s underpinnings — a permanent mise en abyme, leaping from abstraction to narrative to reality.

The show is only truly over upon reading Dennis Cooper’s text, which is handed out to the audience. They can read it whenever they wish after leaving the theatre. This text takes on the form of a short novella, published with Editions P.O.L, ostensibly written years later by the young boy, who has by then become a writer. In the young man’s novella, which appears to be partially autobiographical and partially fictional, his relationship to the woman, and who is possibly his late mother, seems to both elucidate and blur what we have just seen. Their very emotional, and now exacerbated, relationship to the world is revealed to be the cause of their muteness and the thing that encourages their necessary relationship to dance and writing.

This game of perception reflects the various modes with which we perceive the world. Rather than isolating different statuses of representation, like for example abstraction, narration, fiction, reality, etc… this show aims to investigate perception’s differing configurations by taking into account the fact that they are always indistinguishable.

History

-

11 May 2015

-

12 March 2015

-

28, 29 January 2015

-

19, 20 February 2014

-

04 February 2014

-

30, 31 January 2014

-

24, 25 January 2014

-

16, 17 January 2014

-

09, 10 January 2014

-

13, 14 December 2013

-

03 December 2013Le Cadran, Automne en Normandie, Evreux (FR)

-

26 November 2013

-

20, 21 November 2013

-

14, 15 November 2013

-

21, 22 October 2013

-

03, 04 October 2013

-

04, 05 September 2013

-

14, 15, 16 August 2013

-

27, 28 June 2013

-

14, 15 June 2013

-

29 May 2013Festival Manifeste, Les Spectacles Vivants - Centre Pompidou et IRCAM, Paris (FR)